Omoiyari is practical. You notice what might help someone feel safer, lighter, more included, and you respond, often before they need to ask. You make space in conversation. You slow your pace to match someone else. You bring what will help without announcing it. You choose words that protect dignity. This is small-scale, human-scale peacebuilding.

So what does it mean to practise omoiyari in Australia, especially when grief is close and the cultural atmosphere is hot with agitation? When the collective nervous system tightens and begins scanning for certainty, the work becomes a different kind of strength: to stay with the ache without turning it into a weapon, and to build social forms that can hold the human being.

Here, Steiner’s threefold social understanding offers a useful map for cultural repair. In the threefold picture, society is healthiest when three realms can breathe in their own way: a cultural and spiritual life free enough for living thinking, education, art, and meaning-making; a rights life that treats people as equal in dignity; and an economic life that becomes associative, cooperative provisioning of needs rather than extraction as the default. When these realms collapse into one logic, community thins, people become functions, and a function cannot feed a soul.

This is also where I want to acknowledge First Nations knowledge systems with care and humility. On this continent there are deep traditions grounded in Country, kinship, reciprocity, responsibility, and continuity. Without appropriating, we can still be guided by the ethical direction: relationship is the substance of life, and place is a teacher. When we listen respectfully to what First Nations people say about community life and gentle ways of living, we are called away from abstraction and back into pattern, where repair becomes a living act carried through relationship.

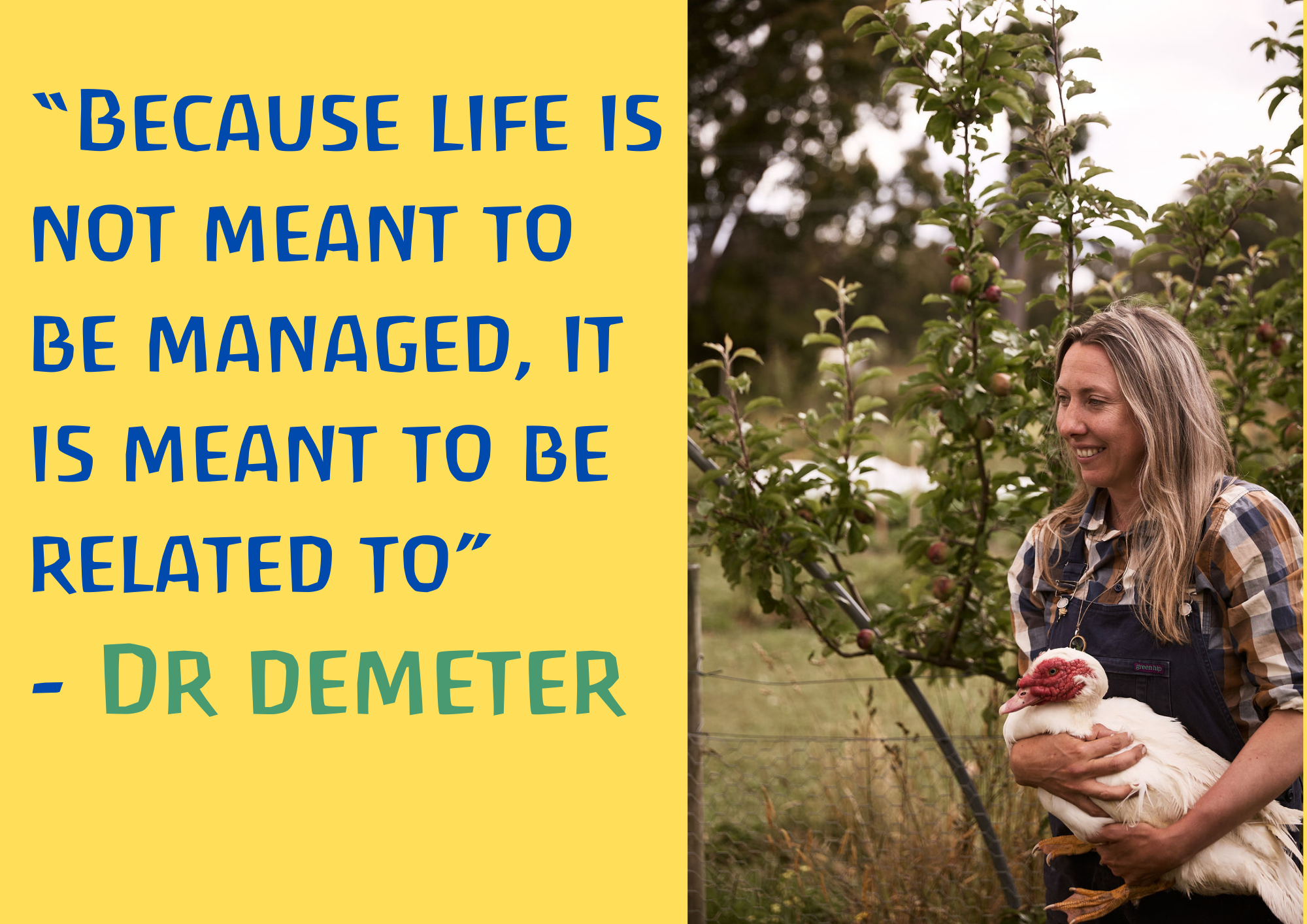

From this ground, I want to offer a nurturing kind of clarity for the forward vision: softness as life-making strength, the capacity to create conditions where something good can grow. This is clarity that illuminates rather than humiliates. It is authority expressed as stewardship, through conditions that help life thrive. In anthroposophical terms, it is the heart remembering it can sense what is true, and the will learning again how to serve life instead of moving from fear.

What might this look like in practice for Australians right now? It can look like rebuilding the village layer of society as deliberate culture-making. Small, repeated gatherings that thicken trust. Shared meals. Working bees. Repair cafes. Community gardens. Parent circles. Walking groups. Spaces where people can be present with difference without being reduced to their opinion. Alongside this, it can look like a civic skill we practise: returning to breath when outrage rises, so the nervous system stays inside the body and care remains capable of relationship. It can look like investing in cultural life that nourishes, including education, arts, local storytelling, and ritual. It can look like strengthening rights life so dignity is protected in practice, not only in principle. It can look like building more cooperative economic forms, including local food systems, co-ops, local energy, and care networks, so meeting needs becomes a practice of cooperation rather than a theatre of fear.

I have witnessed both the absence and the presence of omoiyari in Australia. I have seen politics harden and pressure erode compassion. I have also seen people show up quietly for one another, and neighbours carry each other through difficult seasons. Tasmania has been one lens for me, because on an island you can feel the social atmosphere quickly, yet this is not only a Tasmanian story. It is an Australian one.

This is the heart of what I want to offer as a continuation of my earlier essays: peace is a practice, outrage is a signal, grief is a threshold. The way through is slower and more human. It is the work of reweaving, rebuilding the social fabric until the binary spell loosens, until belonging becomes more normal than contempt, and until we remember that the opposite of polarisation is relationship strong enough to hold difference.

Omoiyari is not a foreign ideal. It is an attention-practice we can speak in our own language: care, neighbourliness, mateship made real, village culture built deliberately through the choices we repeat. The invitation now is simple and practical: to become cultivators of life, creating conditions where what is most human in us can grow again.

With love and Con Viv,

Emily / Dr Demeter

Emily Samuels-Ballantyne, PhD / Dr Demeter is a Tasmanian-based regenerative designer, biodynamic herb farmer, educator, and policy-oriented researcher. Her work brings together living systems design, conviviality, and place-based governance to help communities build conditions for care, belonging, and ecological repair. She leads Magical Farm Tasmania, a small farm and learning site, and Regen Era Design Studio, a design studio supporting community scale food systems, regenerative enterprise, and public sector reform. She is also developing Con Viv, a long-form body of work and practical framework for relationship-centred agriculture and cultural renewal.

Emily’s peace activism began early. At eleven, she attended an international peace conference in Japan with children from fifty-six countries. Since then, she has continued supporting the Asian-Pacific Children’s Convention in Fukuoka as a peace ambassador and chaperone for Australian children. Her public writing and community work focus on restoring the social fabric through everyday practices of attention, cooperation, and locally rooted cultural life.